Even under Nazi Germany’s ruthless rule, sport kept the Dutch people going. Football remained largely untouched by the occupiers and attracted thousands in attendance.

But the pitches, courts, and fields also harboured heroes of the Dutch resistance, who fought for the country’s freedom by giving shelter to Jewish families, sabotaging German war efforts, being the extension of the Dutch government-in-exile in London, and standing up to oppression.

During the week we celebrate 80 years of freedom, we tell the stories of the resistance heroes who lived double lives on and off the theatre of their sport.

Episode 1: The Dutch resistance hero who sparked his football club's fire

Episode 2: The resistance hero who captained PSV to their first title

Boxing school Olympia

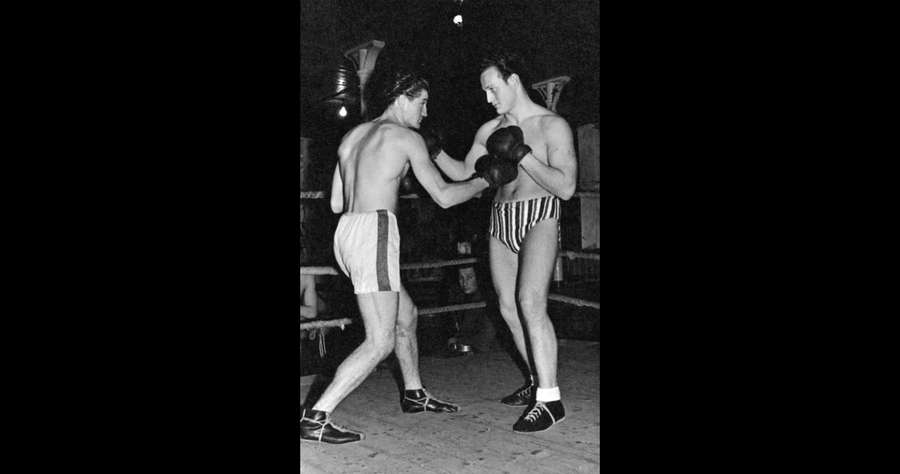

When you look at the earliest days of the Dutch resistance, you’ll very quickly end up at boxing school Olympia in Amsterdam. Olympia was a predominantly Jewish boxing school founded in 1928 by Dutch bantamweight champion Joop Cosman, who opened the school in the Jewish Neighbourhood in Amsterdam.

The club attracted an array of boxers, of whom 90% were Jewish, and some were national champions. David Zilverberg won the Dutch flyweight championship in 1938, Barend Groenteman was a provincial champion, and Isaac Brander had won several tournaments.

The club travelled to Berlin in 1935 for a boxing tournament, three years after Adolf Hitler took control of the country. “We had never experienced antisemitism in that way,” said Cosman years later. “When we told Jews in Amsterdam how the Nazis treated German Jews, they didn’t believe us. It was unbelievable.”

Even before Nazi Germany invaded and occupied the Netherlands, Olympia carried an activist role in the Amsterdam scene. Members of the Dutch Nazi party NSB were often targeted by members of Olympia, of whom Zilverberg and Bennie Bluhm put up posters saying “Fascism is murder.” The two were approached by a group of NSB members, and they let them. “We were boxers, we could use our hands well, run well,” Bluhm said decades later.

When the war reached the Netherlands, the Amsterdam boxers knew they could defend the vulnerable. Sam Cosman therefore created an fighting group, or knokploeg – the first Jewish fighting group in the Netherlands – with tens of boxers from Olympia and the areas of Kattenburg and Jordaan in Amsterdam. “We weren’t afraid. That Jews are naturally cowardly is a fairy tale. That's what that fighting group proved,” said Cosman.

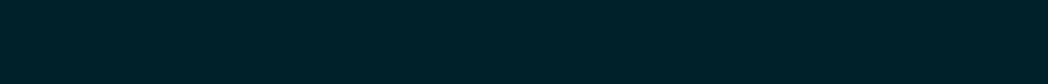

The fighting group professionalised itself by getting former Olympian Ben Bril as a fighting coach. Bril qualified for the 1928 Olympics, where he made the quarter-finals in the flyweight class. The Dutch flag-bearer for that tournament was Sam Olij, whose sons would later join Olympia as well.

Tough resistance

Cosman’s squad did not use guns, but only their trusted hands and iron bars, which they also used on February 11th, 1941.

40 Nazis marched through Amsterdam, starting from the Blauwbrug to Waterloo Square, all the while singing antisemitic songs. About 90 members of Cosman’s knokploeg were waiting in the shadows of Waterloo Square on a chilly, foggy evening. “And there we jumped them. Those guys were completely surprised and flew in all directions, most of them back to the Blue Bridge. But a few just ran in the other direction,” Cosman recalled.

One of the Nazis who marched there was Hendrik Koot, an infamous member of the NSB party and its Nazi paramilitary force. Koot marched through the streets with his son amongst the 39 other NSB party members, and was fatally struck by one of the fighting group members.

Koot died of his injury three days after the fights and the Nazis took this as a reason to intensify the persecution of Jews in Amsterdam, starting the first razzias in Amsterdam. These razzias sparked the famous February strike, in which Gerben Wagenaar was a leading figure.

Several members of the fighting group got arrested, and Ben Bril, who stood on the sidelines, got sent to the concentration camp Westerbork along with his family after Sam Olij, Ben’s former friend and 1928 Olympic flag bearer, betrayed the Bril family.

Ben Bril eventually survived the concentration camps and became a boxing referee, appearing at several Olympics in this role.

Joop Cosman, meanwhile, escaped time and time again from the grasp of the Nazis. The founder of Olympia had built a hiding spot under the boxing ring in his school – one which was used by many as the Nazis continued hunting down the Jews in Amsterdam. Boxing lessons continued, and Cosman survived, also thanks to former Dutch Olympic swimmer Piet Ooms.

Almost nobody else in the fighting group did, except for Bennie Bluhm. Bluhm was a crucial fighting group member and avoided immediate persecution after the fights in February 1941. Bluhm joined a communist resistance group which sheltered people in hiding and provided food stamps before getting deported for the Arbeitseinsatz, the Nazi forced labour deployment. Bluhm survived because of his boxing skills, which the Nazis forced him to show in exhibition matches which he was forced to lose.

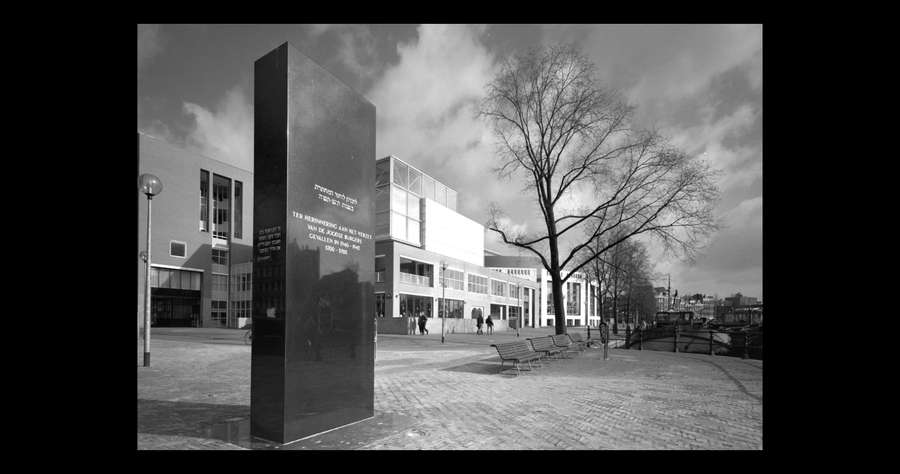

When the Canadians liberated concentration camp Westerbork, Bluhm was a loud voice for recognition of the Jewish resistance heroes which were the very first to act up against the Nazi paramilitary forces. His efforts and those of many more were honoured 43 years after the war, when the Amsterdam city council placed a monument for the Jewish resistance in the city centre.

Bluhm, who died two years prior, was not there to see it, but knew that his group, the first Jewish resistance group, paved the way for courage and freedom.